Where Does California Collect Money For Road Maintenance

Road funding in Michigan takes several forms. Federal funding comes from the Federal Highway Administration's Highway Trust Fund, which is funded by federal gasoline and diesel taxes. State funding typically comes from state fuel taxes, vehicle registration fees, income taxes and supplemental appropriations from the Legislature. Counties, cities and villages besides provide funding for their own roads through road millages, general taxation revenue and via special cess districts. Public Act 51 of 1951, commonly referred to as but "Act 51," governs how state acquirement for roads and bridges is allocated and spent, with some of it defended for state roads and others shared with local governments for their use.[22]

Federal Road Funding

Federal road funding from the Highway Trust Fund comes primarily from the federal eighteen.4 cents-per-gallon gasoline tax and 24.4 cents-per-gallon diesel revenue enhancement. Federal highway funds are available for projects identified equally federal-aid-eligible highways.[23] Federal funds provide an lxxx pct match of local or state funding for eligible projects and cannot be used for routine maintenance.[24]

A common misperception is that Michigan is a "donor state" with regards to the federal Highway Trust Fund, pregnant taxpayers pay more in federal fuel taxes than they receive in federal highway funding. According to data obtained by the Detroit Costless Printing in 2014, Michigan has non been a donor state since 2003. For example, Michigan paid $1.01 billion to the Highway Trust Fund in 2012 just received $ane.05 billion from information technology.[25] Federal highway funding makes upwards a little less than 30 percent MDOT's upkeep.[26] MDOT receives 75 percent of Michigan'southward federal road funding, with county road commissions and cities and villages sharing the remaining 25 percent.[27]

Michigan Fuel Taxes and Vehicle Registration Fees

Acquirement from Michigan's 26.iii cents-per-gallon gasoline and diesel fuel taxes and its vehicle registration fees make up the bulk of the acquirement that goes into the Michigan Transportation Fund. Coin from the fund is and then disbursed to MDOT, county road commissions and cities and villages. Vehicle registration fees contributed $1.2 billion to the MTF in 2017 while fuel taxes contributed $i.4 billion. Vehicle championship fees contributed $40 million.[28]

Michigan's gasoline and diesel taxes were set at xix cents per gallon and 15 cents per gallon, respectively, in 1997 and not indexed for inflation. They were increased in 2017 to 26.3 cents per gallon and will exist indexed to inflation commencement in 2022. Vehicle registration fees were also increased by an average of 20 percent in 2017.[29]

The state too assesses a 6 pct sales tax on fuel purchases, but nearly all of that acquirement is dedicated to public schools and local governments.[30] Electric vehicles are assessed a $100 annual surcharge and hybrid vehicles are assessed a $30 annual surcharge to offset the fact that owners of these vehicles either exercise not pay fuel taxes or pay substantially less than owners of conventional vehicles practice.[31]

Gasoline taxes for passenger cars are nerveless at the pump. Diesel fuel taxes for interstate trucks operates much differently. Interstate trucks are covered by the International Fuel Tax Agreement, which provides a method for truck drivers to pay the advisable amount of fuel taxes based on how many miles they drive in each jurisdiction. Truck drivers maintain a logbook that records the number of miles traveled in Michigan, summate the diesel that was required to travel those miles, and then pay the Michigan diesel tax on that amount of fuel, plus the half dozen pct sales revenue enhancement.[32]

The registration fees for passenger cars are based on the vehicle's age and estimated base price.[33] Registration fees for commercial trucks are based on the truck's gross vehicle weight and range from $590 per year for trucks weighing 24,000 pounds to $three,741 per twelvemonth for trucks weighing over 160,000 pounds.[34]

At that place are exceptions, notwithstanding. Trucks used as moving vans or to operate a carnival go a special registration rate that is 80 per centum of the usual charge per unit.[35] Information technology is unclear how much this reduces revenue to the MTF. Trucks that carry farm commodities, milk and logs likewise pay a substantially reduced registration fee that is not based on gross vehicle weight but instead is equal to 74 cents per 100 pounds of the weight of the tractor or empty truck.[36] This reduces MTF revenues past an estimated $40 million per year.[37] Approximately one-tertiary of commercial trucks registered in Michigan pay this reduced registration fee.[*]

The annual registration fee paid by subcontract, milk and logging trucks is often less than that for a typical passenger machine. In Dec 2012, farm trucks paid an boilerplate almanac registration fee of $72.21, milk trucks paid $129.lxxx and logging trucks paid $107.30.[38] The price of a typical passenger car'south registration fee was approximately $120.[39]

There is a widespread belief that Michigan'due south weight restriction laws for commercial trucks are more generous than those in other states and this is largely responsible for the poor condition of Michigan's roads. Most states use a truck's "gross vehicle weight" to determine the maximum allowable weight on the route. A 1982 federal law limits GVW on federal-aid eligible roads to 80,000 pounds for an 18-wheel truck. Michigan instead uses beam load restrictions, which set the maximum commanded weight on a single axel. This allows for trucks weighing in backlog of 80,000 pounds on Michigan roads, with a maximum of 164,000 pounds spread over xi axles. Michigan'southward weight restrictions are grandfathered in under the 1982 police. If Michigan repealed them, it could non reinstate them and would have to operate under the federal limits.[forty]

According to MDOT, pavement inquiry shows that a single heavy truck does less pavement harm than two lighter trucks conveying the same combined load. This is, in function, because the weight-per-axle tin be less for a single truck pulling two trailers compared to that of ii lighter trucks each pulling a single trailer. MDOT also argues that repealing Michigan's police force would add 10,000 to 15,000 trucks on the road, resulting in increased traffic and business organization costs.[41] However, how Michigan's weight limits are set is less important than the question of whether the taxes and fees trucks pay is in line with the damage they do to Michigan's roads. As shown afterwards in this study, the fuel taxes and registration fees trucks pay are less than the estimated cost of the pavement harm they inflict.

How Michigan Transportation Fund Revenue is Distributed

Several government units, both state and local, receive money from the Michigan Transportation Fund, including the Michigan Department of Transportation, county road commissions, cities, villages and townships.

Michigan Department of Transportation

Michigan vehicle registration fees and fuel taxes generated approximately $2.6 billion in revenue in financial yr 2017. Approximately $24 million of this was used for authoritative overhead, with the biggest component being $20 meg used to operate the Secretary of State. A total of $63 million in transportation revenues went to the Economical Evolution Fund and the Recreation Improvement Fund. Another $154 million was spent on administrative grants, debt service and other grant programs. After these deductions, approximately $2.3 billion in revenue was distributed to MDOT, canton road commissions, and cities and villages to maintain and repair roads and bridges.[42]

The Economic Development Fund was created in Human activity 51 to fund transportation improvements that back up private investment and job cosmos. Its annual written report cites five categories of road improvement projects eligible for assist: for targeted manufacture evolution and redevelopment, to reduce urban traffic congestion, to create an all-flavour route network in rural counties, to support the development of commercial forests, and to support an all-flavour road network in urban areas of rural counties.[43]

Approximately $41 million in MTF revenues went to the Economic Development fund in financial year 2017.[44]

Two pct of gas tax revenue go to the DNR's Recreation Improvement Fund, representing fuel taxes paid by off-road vehicles and motor boats.[45] The Recreation Improvement Fund, in combination with the Michigan State Waterway Fund, helps fund the operation, maintenance and development of recreation trails, land restoration, inland lake cleanup and harbor and dock infrastructure.[†]

Some other 10 percent of the MTF is earmarked for the Comprehensive Transportation Fund. Money from that fund is used to support public transportation throughout the country. Most of this money is allocated, based on a formula, to local transit agencies. In financial 2018, close to $250 meg was disbursed from the MTF for such purposes.[46]

The $2.3 billion remaining in the MTF afterwards the monies described above were allocated were disbursed based on the post-obit allocations: 39.1 percent goes to MDOT for the state trunkline fund, 39.one percent goes to county road commissions and 21.viii per centum goes to cities and villages.[47] Ane percent of the Act 51 distribution to county route commissions is set aside for snow removal in counties that receive more than than 80 inches of snow annually.[48]

County Road Commissions

Deed 51 distributes MTF funds to county route commissions based on a number of factors. How much each county receives depends on how many miles of certain types of roads information technology has, how many vehicles are registered there, its population and its almanac snow.[49] Graphic xi summarizes these factors.

Graphic 11: MTF Distribution to Canton Road Commissions

| Criterion | Per centum of MTF Distribution | Factor |

| Primary Road Mileage | six.iv% | $2,164 per mile |

| Local Route Mileage | 16.4% | $ii,374 per mile |

| Urban Road Mileage | 9.9% | $12,390 per mile for urban principal roads, $2,065 per mile for urban local roads |

| Vehicle Registrations | 47.ix% | 37ȼ per dollar nerveless in the canton |

| 1/83rd Share to Each Canton for Main Roads | nine.6% | $ane,056,287 per canton |

| Rural Population | 8.eight% | $sixteen.88 per person |

| Snowfall Removal | 1% | Based on average wintertime maintenance costs and actual snowfall |

| Total | 100% | $906,168,948 to counties |

Source: Michigan Department of Transportation. Information from July 2017.

As seen from Graphic 11, the number of vehicle registrations within a particular county is the largest determinant of how many MTF dollars a county receives. If a county has, say, 5 percent of all vehicle registrations in the state, then the county will receive five percent of MTF dollars that are distributed based on vehicle registrations.

Each calendar month, MDOT releases a gear up of distribution factors that allows a canton to determine the amount of MTF dollars it will receive based on its population and road mileage.[50] The factors are found past taking the full amount of MTF dollars available for a detail category and dividing that sum by the county's population or number of road miles in that category. For case, full MTF dollars available for principal county roads is divided by the total miles of primary county roads to arrive at $2,164 per mile. County road commissions would then multiply the number of primary county roads in their respective counties by $two,164 to determine their MTF allocation for principal road miles. The road commissions would brand a like calculation for each row in Graphic 11 to decide their total MTF distribution for the year.

The nearly recent allocation factors are given in the concluding column in Graphic 11. Each county receives $ane,056,287 from the MTF plus 37 cents for every $1 residents in the canton paid in vehicle registration fees. Rural areas, defined as areas outside of an incorporated municipality, receive an additional $16.88 per resident. Counties with urban roads receive $12,390 per mile for urban primary roads and $2,065 per mile for urban local roads. All counties receive $2,164 per mile for principal roads and $two,374 per mile for local roads.[51]

It is non clear whether urban counties or rural counties disproportionately do good from how MTF funds are distributed. On i paw, urban counties have more than drivers, which amounts to doing more than damage to the roads. On the other mitt, rural counties take a large number of roads relative to their population, and it would be more than difficult to maintain these roads if MTF dollars were distributed based strictly on population.

Graphic 12 illustrates this tradeoff. Counties are grouped into urban and rural counties based on U.Due south. Census data. Urban counties receive, on average, almost five times more MTF dollars than rural counties. However on a per capita basis, rural counties receive 57 percent more MTF dollars than urban counties. Rural counties have three times more than miles of road per capita than urban counties. Thus there is a tradeoff in allocating MTF dollars on a population basis, which would benefit urban counties, and a miles of roads footing, which would benefit rural counties. The current MTF distribution formula tries to strike a residuum between this tradeoff.

Graphic 12: MTF Distributions for Urban and Rural Counties, 2017

| Urban | Rural | |

| Boilerplate MTF Distribution | $23,029,055.57 | $iv,890,398.72 |

| Average Population | 149,609 | 24,598 |

| Distribution Per Capita | $147.35 | $257.53 |

| Average Miles of Roads | 2,136.24 | 984.78 |

| Miles of Roads Per Capita | 0.0143 | 0.0400 |

Source: Author'southward calculations based on data from July 2017 MDOT reports and data from the U.South. Demography.

Graphics 13-sixteen illustrate average route and span atmospheric condition for urban versus rural counties. They show that there is substantially no departure in average route conditions in urban versus rural counties. And there are but minimal differences in the boilerplate condition of bridges. This suggests that Act 51 might be striking the right residual in allocating MTF dollars.

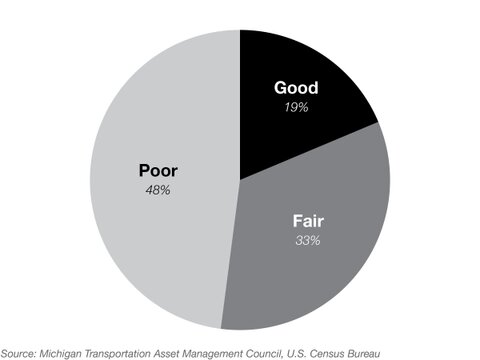

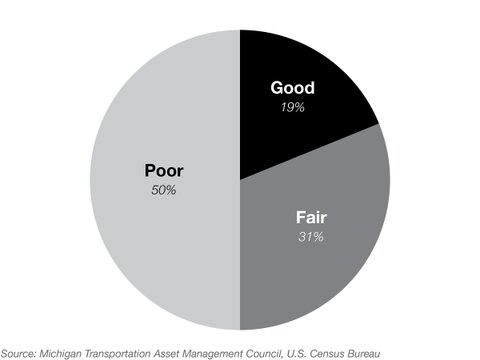

Graphic 13: Boilerplate Road Conditions in Rural Counties, 2017

Graphic 14: Average Road Conditions in Urban Counties, 2017

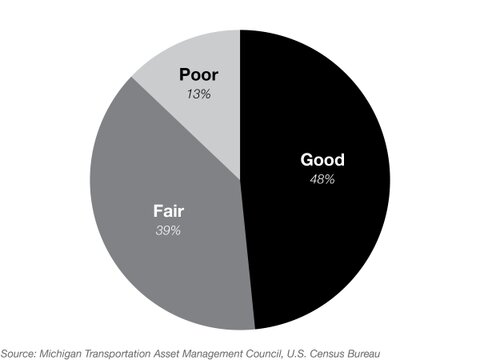

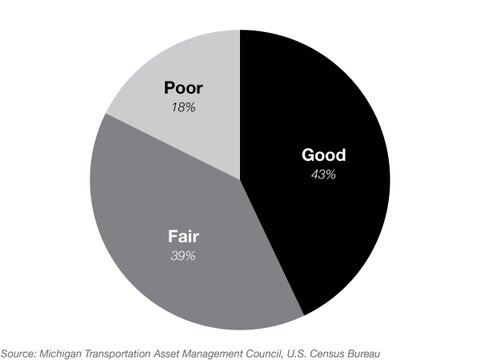

Graphic 15: Average Bridge Conditions in Rural Counties, 2017

Graphic 16: Average Bridge Condition in Urban Counties, 2017

Cities and Villages

Seventy-five percent of MTF funds distributed to cities and villages are used for major streets and 25 percent are used for local streets. Lx percent of the major and local street distribution is based on population and 40 percentage is based on road miles.[52] The MTF funds used for local streets must be matched by the municipality.[53]

As it does with counties, each twelvemonth MDOT uses resource allotment factors to distribute MTF revenue to cities and villages. The distribution is based on population (as of the latest U.Southward. Census) and road miles.[54] Unlike counties, cities and villages with a larger population get a larger per capita allocation from the MTF. That is because the number of miles of major streets in a city or hamlet is multiplied by a population factor to determine the MTF distribution. This population factor increases with the city or village's population. Graphics 17 and 18, which employ data from Plante Moran'due south "Estimated Act 51 Revenue Worksheet" for the fiscal year catastrophe June 30, 2018, illustrates the range of the factor:[55]

Graphic 17: MTF Distribution to Cities and Villages

| Major Streets | ||

| Criterion | Amount | Cistron |

| Population | $43.96 per person | due north/a |

| Major Street Mileage | $12,660.75 per mile | See Graphic eighteen |

| Trunkline Mileage | 2 ten $12,660.75 per mile | See Graphic 18 |

| Local Streets | ||

| Population | $14.65 per person | n/a |

| Local Street Mileage | $3,335.25 per mile | n/a |

Graphic 18: Population Factors

| Population | Factor | |

| From | To | |

| 1 | 2,000 | 1.0 |

| 2,001 | 10,000 | one.1 |

| twenty,001 | thirty,000 | 1.ii |

| 30,001 | 40,000 | ane.three |

| xl,001 | l,000 | i.4 |

| 50,001 | threescore,000 | i.5 |

| 60,001 | seventy,000 | 1.6 |

| 70,001 | 80,000 | i.seven |

| lxxx,001 | 95,000 | 1.eight |

| 95,001 | 160,000 | i.ix |

| 160,001 | 320,000 | 2.0 |

| Over 320,000 | See below | |

Notation: For a population over 320,000, a factor of 2.1 is used plus an additional factor of 0.i for every 160,000 of population over 320,000

A city or hamlet receives $43.96 per person for major streets and $14.65 per person for local streets. It also receives $3,335.26 per mile of local streets. There are a couple of things to note about how major street mileage funds are distributed. First, the amount per mile increases as the municipality'due south population increases. A municipality receives $12,660.75 per major street mile times its population factor. Thus a urban center or village with 1,000 residents would receive $12,660.75 x 1.0 or $12,660.75 per major street mile. A city or village with 100,000 residents would receive $12,660.75 ten 1.9 or $24,055.iv per major street mile. Michigan'due south largest city, Detroit, with a population of 713,777 in the 2010 demography would receive $12,660.75 x 2.3 or $29,119.70 per major street mile. Thus, major street mileage funds are skewed toward large cities.

Second, some cities as well become funding for trunkline miles. This funding allotment, available to cities with over 25,000 residents, is based on a formula: the urban center's population factor multiplied by the number of trunkline miles within it. This resource allotment heavily favors Detroit, which has 22 percent of all trunkline miles in the state that run through cities with a population of 25,000 or more.[‡] Since Detroit'southward population factor is two.3, this trunkline mileage distribution nets the metropolis an additional $17 meg per twelvemonth.

There is no articulate reason why this distribution for trunkline mileage exists. As the House Fiscal Agency points out, maintaining trunklines within municipal boundaries is the responsibility of MDOT, not the municipality.[56] Cities and villages with a population over 25,000 exercise accept to contribute funds toward trunkline improvements, but their contribution is small-scale. Cities with a population over 50,000 accept to pay 12.5 percent of the project'due south cost, cities with a population between 40,000 and l,000 pay xi.25 percent, and cities with a population between 25,000 and 40,000 pay eight.75 percentage of the cost.[57] Express access highways, such as interstate highways, are exempt from this cost sharing requirement.[58] This exemptions benefits cities such as Detroit, given the numerous miles of express access highways that run through it.

In add-on to these issues, the per-mile trunkline distribution is double what is allocated for major street maintenance and repair, which cities are responsible for maintaining. Approximately $61.5 million was distributed to cities for trunkline maintenance in 2017, even though cities are not responsible for maintaining these roads.[§]

In short, distributions from the Michigan Transportation Fund to cities and villages function in a similar way to counties in that the distribution is based on population and road mileage. Multiplying major road mileage past a population cistron and giving municipalities with a population over 25,000 an allocation based on trunkline miles (which is also multiplied by the population gene) skews the distribution toward larger cities. Coin distributed to counties is non, by dissimilarity, skewed this mode.

Counties, cities and villages take some flexibility in how they spend MTF dollars. With some exceptions, they can transfer some of their earmarked funding for other purposes. For example, counties can divert up to 30 pct of their funding earmarked for primary roads to local roads, if they choose. Conversely, they can shift 15 percent of their funding earmarked for local roads to maintaining and constructing primary roads. They can spend another 15 percent of local road funding on primary roads, in the example of an emergency or with the specific blessing from MDOT.[59] Cities and villages tin can likewise use MTF funding earmarked for major streets on local streets, provided that the piece of work is for maintenance and not construction and that it does not exceed 50 per centum of the municipality'due south major street funding, unless it adopts an asset management process and sends a re-create of the programme to MDOT.[60]

Local Road Millages

Some counties, townships, cities and villages supplement their MTF distribution with local property tax levies. Graphic 19 gives information on these local road millages, based on data from 2017.

Graphic 19: Local Road Millages

| Unit of measurement of Government | Number With Road Millage | Total Units of Government | Pct with Road Millage | Average Millage Charge per unit |

| County | 27 | 83 | 33% | 1.2298 mils |

| Township | 472 | 1240 | 38% | i.7248 mils |

| City/Village | 150 | 533 | 28% | two.7235 mils |

Source: Michigan Department of Treasury

A manufacturing plant is a $1 tax per $1,000 of assessed taxable value, which is approximately equal to half of the sale cost of the property. A homeowner with a $200,000 firm in a city levying a two.7235 millage would owe a $272.35 holding revenue enhancement toward the urban center's roads. It'due south difficult to decide the impact these local millages have local governments' ability to maintain their roads, as they depend heavily on the millage rate and the local holding value in the jurisdiction. They could, however, exist a significant source of route funding for some municipalities.

There is some bear witness that road millages ameliorate route quality for cities and villages. Nevertheless, it is difficult to determine the relationship between the road conditions and route millages in a county because both counties and townships tin levy millages, but PASER data is only available at the canton level. With this limited data, it would be impossible to know if an individual township'due south road condition was improved by its millage.

Since cities and villages are responsible for maintaining sure roads and PASER data exists at the city and hamlet level, information technology is possible to calculate a correlation betwixt municipal millages and road weather. For cities, there is a potent correlation betwixt the two. Fifty-eight percent of roads in cities without a road millage are in poor condition, on average. If a city has a road millage, each manufactory is correlated with a six-indicate reduction in the pct of its roads that are in poor condition, a result that is statistically significant. In other words, a city with a one-mill road millage will have 52 pct of its roads in poor condition, on average, compared to 58 percent for a city with no road millage.

The correlation is weaker for villages. Forty-vii percent of roads in villages without road millages are in poor condition. Each mill of a road millage is only correlated with a three-tenths of a point reduction in the percentage of roads in poor condition, a result that is not statistically meaning. One potential explanation for this is that villages have smaller populations than cities and typically less taxable holding value, so a road millage in a village might not collect as much revenue as a road millage in a city, limiting the number of improvements the hamlet can undertake. A village might just need a substantially higher millage rate than a urban center to become the dollars needed to ameliorate its boilerplate quality in a style that would make a significant divergence. The average route millage for villages is iii.3 mils, one mill higher than the boilerplate rate for cities.

Special Assessment Districts

Neighborhood streets in a subdivision inside a township are under the jurisdiction of the canton route commission. County route commissions typically maintain, repave and reconstruct these roads often, likely because they give priority to other, more than-travelled roads under their jurisdiction. Nevertheless, residents who wish to have these types of roads maintained can petition to create a "special cess district" for the purpose of levying a tax on property owners in a defined area. Sorry taxes must increases the value of backdrop in the commune.[61]

Residents in a proposed Lamentable must get 50 pct of property owners to sign a petition for the Distressing plan to movement forward. In one case this happens, a public hearing is held for residents to limited support for or opposition to creating a commune. If a majority of the lath of directors of the county road commission votes to create it, the work to be supported by the special cess is bid-out and a 2nd public hearing is held to discuss the required costs. If final approval is given past the lath to authorize the piece of work and assessment, the SAD is created and the cost shared amongst its residents.[62]

According to the Michigan Department of Treasury, only three municipalities have SADs dedicated to route funding: the townships of Clarence, Porter and Lenox in Calhoun, Van Buren and Macomb counties, respectively. The vast majority of special assessment districts used in the state are for fire services.[**]

MTF Revenue Trends

To summarize, virtually half of all canton, city, and village roads in Michigan are rated equally being in poor condition, with over half of Michigan's trunkline roads projected to exist in that state by 2024. How did Michigan's roads end upward in this status?

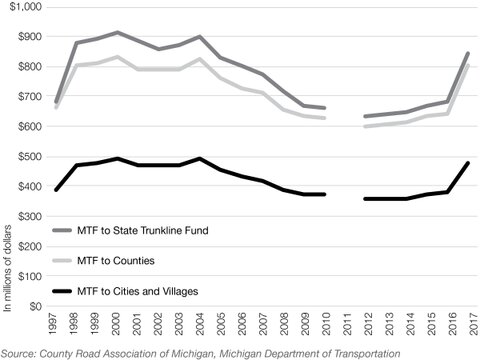

The main trouble appears to be that MTF revenues have not kept upward with inflation, as shown by Graphic twenty. Several years near the start of the century were particularly difficult for the fund, with revenues falling fifty-fifty without adjusting for aggrandizement.

Graphic 20: Inflation-adjusted MTF Acquirement Distributions, 1997-2017

Before the fuel tax and vehicle registration fee increased in 2017, MTF revenue had fallen by 25 pct from its peak in 2000. Even with the tax and fee increment, MTF revenue still remains approximately $70 million below that peak.

Complicating matters farther, the cost of maintaining and amalgam roads steadily increased. In other words, the real purchasing power of the money regime officials have to spend on road maintenance declined substantially.

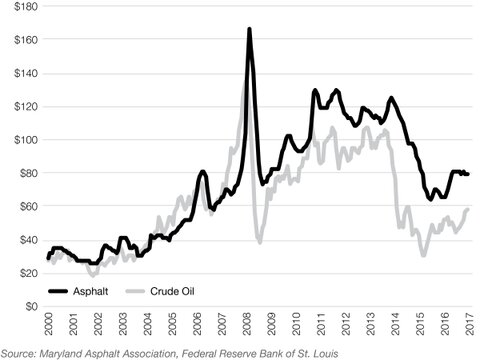

For instance, the price of crude oil plays a substantial function in determining how far road dollars will go as it is an important ingredient in asphalt. Graphic 21 plots the monthly toll of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude oil versus the monthly cost of a ton of liquid asphalt. Since the price of a ton of cobblestone is roughly five times that of a barrel of crude oil, dividing the price of asphalt by five makes the relationship betwixt the two easier to run across. Note that the 2 lines appear to move in tandem.

Graphic 21: Toll of Crude Oil vs. Price of Ton of Liquid Asphalt

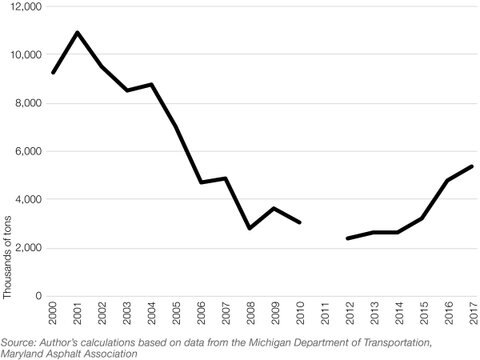

Graphic 22 illustrates how much asphalt could be purchased if all MTF revenue was used merely on asphalt. Patently, MTF revenues are used for things other, likewise. This effigy simply shows how fuel tax and vehicle registration fee revenue are not keeping up with the increasing cost of asphalt. Between 2008 and 2015, MTF revenues were simply able to purchase, on average, less than ane-quarter the corporeality of asphalt as in the year 2000. Even after the fuel taxation and vehicle registration fee increase in 2017, MTF revenues could only buy one-half the cobblestone they could in 2000.

This problem is worsened by the fact that drivers might respond to higher rough oil prices — and increased gas prices — by driving less. Rising crude oil prices discourages drivers from spending on fuel, which reduces the country'due south tax revenue for roads. At the aforementioned time, the cost increases in crude oil makes cobblestone more expensive. In other words, increases in rough oil prices damage road financing from both ends: they reduce revenues and make road piece of work more expensive.

Graphic 22: How Much Asphalt MTF Revenues Could Purchase, 2000-2017

Graphic 23 describes the problem in more item. Between 2000 and 2016, MTF revenues increased an average of 0.8 percent per year. During the same time menstruation, inflation (equally measured by the consumer toll index) averaged 2.1 pct per year and rough oil prices increased by an boilerplate of 5.5 percent per year. Asphalt prices increased by an average of 7.three percent per year.[††] The tabular array below also illustrates this tendency for the years before the Corking Recession. Between 2000 and 2007, MTF revenues increased by an average of 1.1 percent per twelvemonth. Inflation averaged 2.7 percent growth annually, while crude oil and asphalt increased past a yearly average of 14.five percent and 11.4 percent, respectively. In short, MTF dollars failed to continue up with costs, which likely impacted the condition Michigan'south roads are in now and projected to exist in the nearly hereafter.

Graphic 23: Purchasing power of MTF revenues, annual average change, 2000-2016

| Period | MTF Revenues | Aggrandizement | Crude Oil | Asphalt |

| 2000-2007 | ane.1% | two.7% | 14.5% | 11.iv% |

| 2000-2016 | 0.8% | 2.1% | 5.v% | vii.3% |

For much of 2001, the nation was in a recession, which the National Bureau of Economic Research estimates ended in November of that year.[63] Only while the rest of the nation recovered post-obit this downturn, Michigan's economy entered a "one-state recession" that lasted until 2007 when the state, along with the residual of the nation, entered the Not bad Recession, which ran from Dec 2007 through June 2009.

Graphic 24 compares the performance of Michigan's economy with the national economy between the end of the 2001 recession and the start of the Great Recession, as well as from the finish of the 2001 recession to 2017. From 2002 to 2007, the national economy grew by an boilerplate of 2.seven percent annually, while Michigan's economy shrank by an average of 0.6 percent annually, equally measured by gross domestic product. Per capita personal income shrank past an average of 0.iii percentage annually in Michigan, while nationally it grew by an average of i.ii percent annually. The Michigan unemployment rate was also, on average, one.6 percentage points higher than the national unemployment rate. As seen from Graphic 24, the national economy outperformed the Michigan economy for the unabridged 2002-2017 time period.

The slowdown in the economy resulted in a slowdown in vehicle miles driven and thus a reduction in dollars going into the MTF. Nationwide, drivers traveled nearly 12 percent more miles in 2016 than in 2002.[64] In contrast, Michigan drivers traveled only 1 percent more miles over the aforementioned period.[65] Thus Michigan'due south route funding experienced a double-whammy: revenue enhancement acquirement went down even every bit the price of maintaining roads went up.

Graphic 24: Michigan vs. National Economy, 2002-2017

| Michigan | |||

| Period | GDP Growth | Unemployment | Per Capita Personal Income Growth |

| 2002-2007 | -0.6% | 6.9% | -0.3% |

| 2002-2017 | 0.four% | 7.nine% | 0.3% |

| National Average | |||

| Period | GDP Growth | Unemployment | Per Capita Personal Income Growth |

| 2002-2007 | two.seven% | 5.iii% | 1.2% |

| 2002-2017 | i.viii% | 6.3% | 1.0% |

[*] In December 2012, there were approximately eighty,000 trucks registered who paid the total registration fee based on GVW and 47,000 registered subcontract, milk, and logging trucks that paid the discounted registration fee. See "Michigan's Truck-Weight Law and Truck-User Fees" (Michigan Section of Transportation), https://perma.cc/ 9EN7-U2QQ.

[†] The Waterway Fund receives 80 percent of the revenue generated from the 2 percent of gas tax revenue that is devoted to the Recreation Improvement Fund. Another 14 pct of this revenue is dedicated to snowmobile trail construction and maintenance. "Where the Money Comes From" (Michigan Department of Natural Resource, 2018), https://perma.cc/3J7M-KYEZ; "Recreation Improvement Fund" (Michigan Department of Natural Resources, 2018), https://perma.cc/ VFT4-UU8L.

[‡] As of Apr 2018, there are i,332.07 miles of trunkline roads running through Michigan cities with a population of 25,000 or more than. Detroit has 290.9 of these miles. "City/Village Population and Mileage: MTF Distribution Calendar month: April, 2018" (Michigan Section of Transportation, May 22, 2018), https://perma.cc/8FKQ-9NJ9.

[§] Trunkline mileage funds are allocated based on two times the population gene, times the number of trunkline miles in the city, times $12,660.75 per mile. "Metropolis/Village Resource allotment Factors" (Michigan Department of Transportation, 2018), https://perma.cc/U9PQ-PTWX.

[**] This information tin be found here: https://eequal.bsasoftware.com/ MillageSearch.aspx.

[††] I use the time menses 2000-2016 because 2017 is an outlier in that MTF revenues increase by 26 per centum due to the increase in the gas tax and vehicle registration fee. This pulls the average for the entire time menstruum up to a 2 per centum increase, which gives a misleading picture nigh what was happening to MTF revenues during this time period.

Source: https://www.mackinac.org/25863

Posted by: riosbroment.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Where Does California Collect Money For Road Maintenance"

Post a Comment